Germany / The 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander looks back at the crucial period in German history between the First World War and the rise of Nazism. The thread that runs through it is the dialogue between 900 multidisciplinary works of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement and the work of the photographer August Sander, People of the Twentieth Century. Supported by the Almayuda Foundation, the exhibition reflects the cultural blossoming that took place during the Weimar Republic and reached its height in Berlin before fading away, snuffed out by the Great Depression of 1929 and Hitler’s ascent to power.

Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity, was the name coined for this movement in 1925 by the art historian Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub when he organised an exhibition with this title at the Kunsthalle in Mannheim in Baden-Württemberg.

By then, a number of years had already passed since Germany had returned to a far more realistic artistic figurative representation. Indeed, the defeat of 1918, the failure of the revolutionary period that followed and then the advent of the Weimar Republic put an end to Expressionism and artists’ idealism. Their urge to distort objective reality through the prism of feelings and emotions gave way to a more neutral, more sober, sometimes colder expression, as occurred with the Bauhaus, founded in 1919 precisely in Weimar.

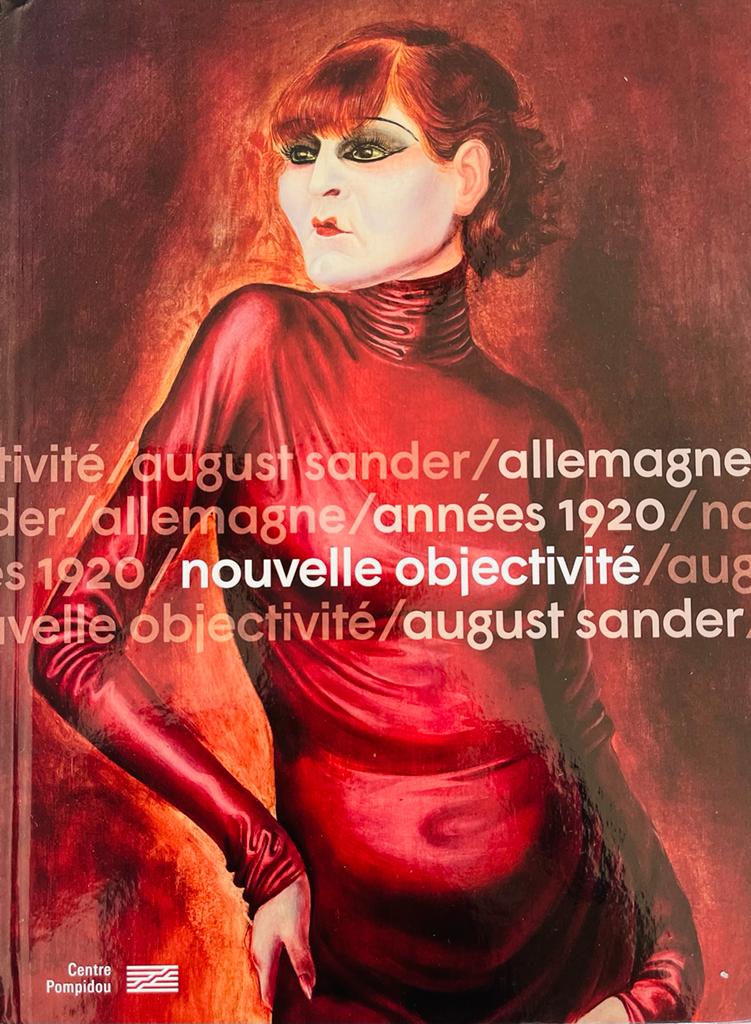

The painter Otto Dix was one of the leading lights of this period and of this new movement. His portrait of the dancer Anita Berber features on the cover of the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, on show at the Centre Pompidou (Paris) from 11 May to 5 September 2022 and thereafter at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (Denmark) until 19 February 2023.

People of the Twentieth Century

Another leading figure of the time and of the movement was the photographer August Sander. He was forty-two years old at the end of the war and became the social portraitist of the Weimar Republic.

Around the middle of the 1920s, he conceived his ambitious project Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts, published in English as People of the Twentieth Century. He continued to pursue this project until his death in 1964, producing hundreds of shots that he divided into seven categories: ‘The Farmer’, ‘The Skilled Tradesman’, ‘Woman’, ‘Classes and Professions’, ‘The Artists’, ‘The City’ and ‘The Last People’.

Given that these are photographs taken during the Weimar years, Sander was interested in his subjects’ social background rather than their physical characteristics. At that time, he subscribed to the ideas of the Kölner Progressive (Cologne Progressives), who embodied socialist utopias.

These artists, who produced compositions featuring exploiters and the exploited alike, embodied socialist utopias. They thus reflected the climate of right-left conflict, the mark of a period that associated a fascination with rationalism and productive efficiency with a social critique of living conditions subjugated to the economy.

An exhibition within an exhibition

Germany / The 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, supported by Almayuda, offers two possible itineraries. The presentation of Sander’s work constitutes a kind of horseshoe situated right at the heart of a multidisciplinary exhibition that brings together painting, photography, architecture, design, film, theatre, literature and music.

A total of some 900 works, all emblematic of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, are grouped into eight sections: ‘Standardisation’, ‘Montages’, ‘Things’, ‘Cold persona, ‘Rationality’, ‘Utility’, ‘Transgressions’ and ‘Downwards look’. These key words alone tell us a lot about this period marked by momentous economic and social events.

The dominant phenomena were the rationalisation of the economy and the fascination with machines, influenced by the American model (Taylorism and Fordism) and capital. This change in methods of production led to the standardisation of ways of life and to veritable sociological revolutions, such as the rise of work for women, who were given the vote in 1919, a long time before French women and just a year after some women got the vote in the UK, though British women did not achieve the same voting rights as men until the Equal Franchise Act of 1928.

At the same time, disillusion and cynicism led to a tremendous moral liberation. To overcome the shame of the war and a defeat that was not understood, Berlin and urban society of the day threw itself headlong into partying and pleasure. This was the era of cabaret, jazz, the democratisation of certain ‘straitlaced’ arts such as the theatre and opera (Brecht and his Threepenny Opera), open homosexuality, transvestism, etc.

All of this is the ‘new objectivity’ that the exhibition seeks to chart. It does so under the watchful eye of Sander, whose portraits are a common thread, a constant reminder that this was a difficult time for the majority of the population and contained within it were all the ingredients of the tragedy to come.

Resonance

The exhibition brings together 900 works by thirty-two artists, among them Otto Dix, a pioneer of the ‘new objectivity’. As well as his portrait of the dancer Anita Berber, mentioned earlier, the display features his painting of the journalist Sylvia von Harden, both of them works that illustrate the ‘Cold persona’ so representative of the Neue Sachlichkeit. Other artists around Dix that we might mention include George Grosz, Alexander Kanoldt, Georg Scholz and Georg Schrimpf, as well as Gerd Arntz, the inventor of the isotype, the precursor of the pictogram, and Paul Renner, the creator of the Futura typeface.

Their works, contextualised by August Sander’s gaze, invite us to consider political comparisons and striking analogies between yesterday and today. This is what Angela Lampe, co-curator of the exhibition and curator of historical collections at the Musée national d’art moderne du Centre Pompidou, expressed on France Culture (Grande Table des Idées [31 May 2022]).

‘We are very pleased that several visitors and commentators have said that there is a genuine resonance with today. I am thinking of the rise of populism, fascism even, latent during these years. There is also an anxiety that is readily perceivable, that same fascination with machines, with technology. Today, we are living in a digital, numerical era. At that time, the radio was the mass medium. There was also transgression, sub-cultures, people’s loss of social position… these themes still resonate a lot today.’

Beware of the 1920s, they might look a lot like today!

Photos : DR

Useful links

https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/